“Ali understood that to be great he needed an external force…. If you fight for yourself, it’s you against others, and this motivates you, but it will never be with the strength that Ali had. Muhammad fought for more than himself. He was fighting for God; his mission was very big…” (A reporter from Sports Illustrated magazine).

We used the words seven years ago or so, following another anniversary of the physical demise of who, without a doubt, has been the most charismatic figure in the history of the sport of gloves and the ring: Muhammad Ali, originally known as Cassius Clay, born in Louisville, Kentucky, on January 17, 1942 and whose death caused by possible sequels of the terrible Parkinson’s disease was on June 3, eight years ago. This note is a tribute to the greatest, Muhammad Ali.

The disease that finally caused his death was diagnosed in 1984 by neurologist Stanley Fahn at New York Presbyterian Hospital.

Ali fought Parkinson’s disease for more than three decades, with the same tenacity he showed in the ring, until, at the age of 74, his strength failed him, and he gave up for good, as a legend of the sports and as an admirable and revered symbol of the fight for the civil rights of his brothers of race and of Islam.

As a professional he was in the ring since 10/29/60 when he debuted with a 6-round victory over Tunney Hunsaker in his hometown of Louisville, Kentucky, a few months after winning the gold medal in the Light heavyweight of the 1960 Rome Olympics, with 4 wins in the event. When in 1981, at the age of 39, he left the ring with 56 wins, 37 by KO, 5 losses, only one before the limit, to his former sparring partner Larry Holmes.

In our long history as sportswriters, we have not written as much about an athlete as we have written about this unique character, the only heavyweight to have dominated the division in 3 different stages (1964-1974-1978) and also the boxer with the greatest universal projection, the best who have stepped on a ring with a pair of gloves on, the one the world has talked about the most and the best known since the origins of his profession, according to historians born about 7 thousand years ago.

In his boxing career, from 1960 until his retirement in 1981, Ali filled the pages of newspapers, magazines, radio, TV, with anecdotes of all kinds, with unforgettable facts recorded for the history of boxing, impossible to summarize, starting with the birth of his passion for boxing aroused as a result of the theft of his bicycle by a petty thief, when he was 12 years old, in his native Louisville; the conquest of the gold medal in the light heavyweight of the Olympic Games of Rome-1960; more than a hundred national amateur titles, the first successes in the professional field; his winning of his first title in February 1964 with a KO7 over the unbeatable Sonny Liston, whom he beat again in a rematch; his refusal to report to the army because he was “an object of conscience”, he said, and “because I am not going to go to Vietnam to kill any Vietcong because no Vietcong has called me a nigger”.

We should also add his victories over the best heavyweights of the time, such as Brian London, Oscar “Ringo” Bonavena, Zora Folley, Henry Chuvalo, Henry Cooper, Cleveland Williams, former light heavyweight champion Archie Moore, the also former heavyweight king Floyd Paterson, Ernie Terrel, 2 over Ken Norton, with whom he lost by decision the first due to a broken jaw from the first round; his refusal to go to the war front cost him the loss of his titles and an absence from the ring for 3 and a half years….

With his unconventional style for the heavyweight (censured by the experts) of moving endlessly from one side of the ring to the other with his arms at his sides, he returned in 1967 with several victories in a row, and on March 8, 1971, at the Madison in New York, he suffered his first defeat against Joe Frazier, by decision. Frazier would later be his great opponent in 2 more fights, won by Ali, the last one on October 1, 1975 in Manila, Philippines, which he won when Frazier could not answer the bell for round 14, in a war to the death in which both finished exhausted and which, it was said, shortened both fighters’ careers in the long run.

After his retirement, Ali devoted most of his time to social activism and from time to time appeared at sporting events. He carried the Olympic torch at the 1984 Los Angeles Games, and later at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics when he lit the cauldron, people saw on TV a physically deteriorated, trembling Ali. In retirement he was showered with awards of all kinds including his induction into the Boxing Hall of Fame in Canastota, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, Sportsman of the 20th Century by Sports Illustrated and BBC London, King of Boxing by the World Boxing Council, Martin Luther King Award and Distinguished Service by the World Boxing Association.

The King of the World, as he proclaimed himself when he first defeated Liston, changed his name because to him Cassius Clay was a “slave name”. In the story we wrote a few years ago about what was undoubtedly Ali’s hottest and most publicized brawl, and certainly the most dramatic and real fight of all time in the history of the ring, took place in Kinshasa, Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of Congo, on October 30, 1974. The fight was promoted by Don King, with Ali and George Foreman in the corners. Foreman was the defending champion and heavy favorite in the betting, however, the spectators overwhelmingly supported the challenger, Ali, who sought to regain his lost throne outside the ring, cheered by the chant “Ali, Bumaye, Ali Buyame” in the local language.

The fight took place in sweltering heat, between 3:00 and 4:00 a.m. local time on Wednesday, October 30, 1974, which was about 5-6 hours ahead of Eastern time in the U.S. and in several South American countries, where it was between 9 and 10 p.m. on Tuesday, October 29. The 20 de Mayo stadium in Kinshasa, formerly known as Leopoldville, the capital of Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of Congo, was the scene of this historic event in Central Africa.

The capacity of the venue, designed to hold some 60,000 people, was almost doubled, with the majority of the spectators composed of passionate fans eager to witness the victory of the 32-year-old challenger, Muhammad Ali, who was 6’3” tall and weighed 216 pounds. These spectators supported him with fervor, especially during the 23 minutes and 58 seconds of the fight, in which he faced the undefeated George Foreman, of equal height and 220 pounds, seven years younger and world heavyweight champion of the World Boxing Association and the World Boxing Council. The cries in the native Lingala language of “Ali, bumayé! Ali, bumayé!” (“Ali, kill him! Ali, kill him!”) echoed throughout the stadium.

To write this article, we went back to the video, mentally returning to October 1974. We recalled the images that never faded. We saw Foreman once again in his red trunks, leaping like an enraged lion or a fighting bull, as he initiated a fighting style and rhythm that did not change in that short time: He would thrust and charge, head down, while Ali, in his white trunks, would shield his gloves over his face and occasionally throw quick hooks, straights and uppers, leaning back against the ropes in what he called the “rope a dope,” while grabbing the champion’s neck with his right or left glove. Foreman threw 50 to 100, even 200 or more punches with full force, which Ali stopped with his arms and forearms, a strategy he kept up for seven long rounds, while his opponent was visibly exhausted. With no major variations, the contest lasted until the eighth round.

In that round, Foreman, who was already extremely exhausted and without strength from throwing so many useless shots, buried his head again. Then, Ali hit him in a dry and firm manner. He clung to him once more, pulled away, clinched and struck again, twice, three more times. With mere seconds left in the round, the challenger unleashed a decisive attack. He rocked his opponent with a left to the head, followed by a right, and a combination of both hands, and suddenly: BAM! The right glove connected squarely on target, and Foreman began a slow, crashing, dramatic fall to the canvas, dislodged, absolutely disjointed, like a heavy cement sack. With that collapse, with his last and only fall, the title fled to a new owner, while the stadium resounded with the euphoric shouts of the thousands in attendance. The champion got up precariously, with wobbling legs. But the referee, former Harlem Globetrotters basketball player Zachary Clayton, had already completed the fateful 10-second count, 2 minutes and 58 seconds into the round.

The dramatic denouement was nothing more than the triumph of intelligence over strength, an affirmation reinforced after having watched the tape over and over again. That fight, publicized by King as “Rumble in the Jungle”, is, we repeat, the most famous, exciting, unforgettable and dramatic fight of all times, whose staging turned 49 years old today, being the reason for a similar note written, repeated and published several times with numerous amendments.

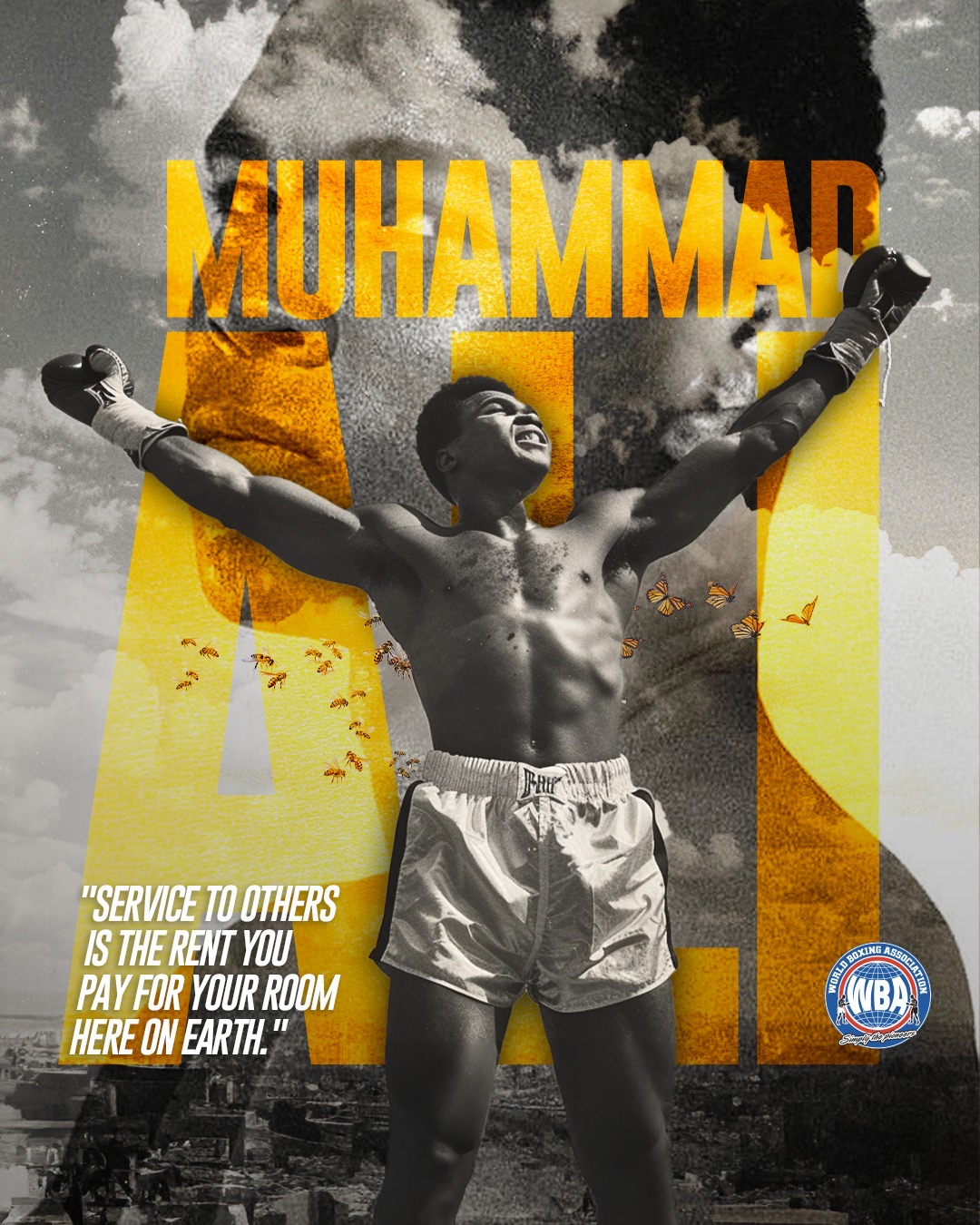

An additional fact: in the seven initial rounds, Ali was ahead in the referee’s and two judges’ scorecards. Zachary Clayton had a score of 68-66, while judges Nourridine Adalla (Tunisia) and James Taylor (USA) had scores of 70-67 and 69. ) scored 70-67 and 69-66, respectively, in favor of Ali, the fighter who flew like a butterfly and stung like a bee, “the greatest and most beautiful of all boxers,” as the irreverent man in the ring who defied the political powers of his country by refusing to join the army in 1967 and who continued to fight for civil rights and his religion, Islam, called himself. After the fight with Foreman, Ali remained in action until 1981. Sick with Parkinson’s disease since 1984, he died at the age of 74, just over two decades after contracting the disease. The cause of his death was septic shock (a serious bodily infection that causes a sharp drop in blood pressure), on June 3, 2016.