There is no particular reason for this second publication of the original written five years ago and published on this website of the WBA, the doyen of boxing governing bodies.

The reason is that a few days ago, in a get-together among friends, someone suggested that we write “something about “Mantequilla”, one of the best Latin American boxers in history, we would say among the 5 best in our region”, was the comment. That is why the article is here again, this time expanded and with the addition of new details:

José Ángel Nápoles, Cuban-Mexican fighter and a boxing legend better known as “Mantequilla passed away in the most pitiful and unfathomable poverty, afflicted with various ailments (diabetes, senile dementia and malnutrition) on August 16, 2019 when he lost his last fight in Mexico City victim of a heart attack at the age of 79.

Napoles was a former World Boxing Association and World Boxing Council welterweight champion, and has been ranked as one of the greatest monarchs of 147 pounds and boxing in general, to such an extent that the prestigious magazine The Ring ranked him 32nd among the 100 best fighters in the annals of the discipline in 2007.

FAREWELL TO CUBA IN SEARCH OF FAME

Born in Santiago de Cuba on 13/4/40, Napoles became a Mexican citizen shortly after leaving his country in the early 1960s following the banning of professionalism by Fidel Castro’s revolutionary government in 1959. When Napoles left his native land, to which he never returned, he had fought 18 fights with 17 wins, one defeat on points and six knockouts. He already stood out as a prospect in a generation of great Cuban fighters that included Luis Manuel Rodríguez (he was world middleweight champion), Douglas Vaillant, Ángel “Robinson” García, Florentino Fernández, among others. The nickname with which he became known came from his feline movement in the ring, elusive, never stopping attacking, passing and blocking punches and with explosive hands.

He made his debut in his home country against Julio Rojas in August ’58 (won by KO1) and added his first loss to Hilton Smith in his eighth appearance. He travelled to Mexico with a record of 17-1-0, as we noted, in the lightweight division and on July 21, ’62, guided by journalist Cuco Conde, his countryman, he made his debut in Mexico City against Enrique Camarena, whom he knocked out in two rounds.

He had more than 30 wins when, on his first trip outside Mexico City, he travelled to Venezuela to face the American L.C. Morgan in Caracas on 30 November 1963, and knocked him out in seven rounds. Seven months later, on June 22, 64, he fought at the Nuevo Circo in the Venezuelan capital against the local idol, the hard-hitting Carlos “Morocho” Hernandez, who later became the first Venezuelan boxer to win a junior welterweight world title.

Nápoles, 24, and Hernández, 22, had similar records of 34-3-0, 17 KOs and 34-3-3, 22 KOs, respectively, which predicted a battle to the death, as indeed it turned out to be. In the fourth round, the Hermandez knocked down Nápoles with a 1-2 right and left for 8 seconds, but “Mantequilla” recovered quickly and in round 7 he cornered Hernández in the ropes and punished him with a barrage of punishments. The intervention of referee Críspulo Salazar stopped the massacre with a dazed, wobbly and defenceless “Morocho”, but still standing.

A short time later, already world-renowned in Mexico and the Caribbean among the lightweights, “Mantequilla” weaved a long string of victories (he lost decisions to Mexicans Tony Perez and Alfredo “Canelo” Urbina and by KO4 to American L.C. Morgan. He got his first title shot on April 18, 1975 at the Forum in Inglewood, California, against Curtis Cokes, WBA and WBC champion, and after an intense battle he finished him off in the 13th round. Two months later he beat him again in 10. He followed with successful defences against Emile Griffith and Ernie Lopez, but Billy Backus (nephew of the famous Carmen Basilio) took the belts from him in December ’70 in 4 rounds. A rematch came half a year later and Napoles won in 8 rounds.

UNEQUAL BATTLE WITH MONSOON

He added consecutive wins over Hedgemon Lewis, Ralph Charles (in 7), Adolph Pruitt (in 2), Ernie Lopez (7), Róger Menetrey, Clide Gray, Lewis again (in 9), Argentine Horacio Saldaño (3) and Aztec Armando Muñiz (2 times by points). In total, 15 exhibitions, with 8 KOs in his favour.

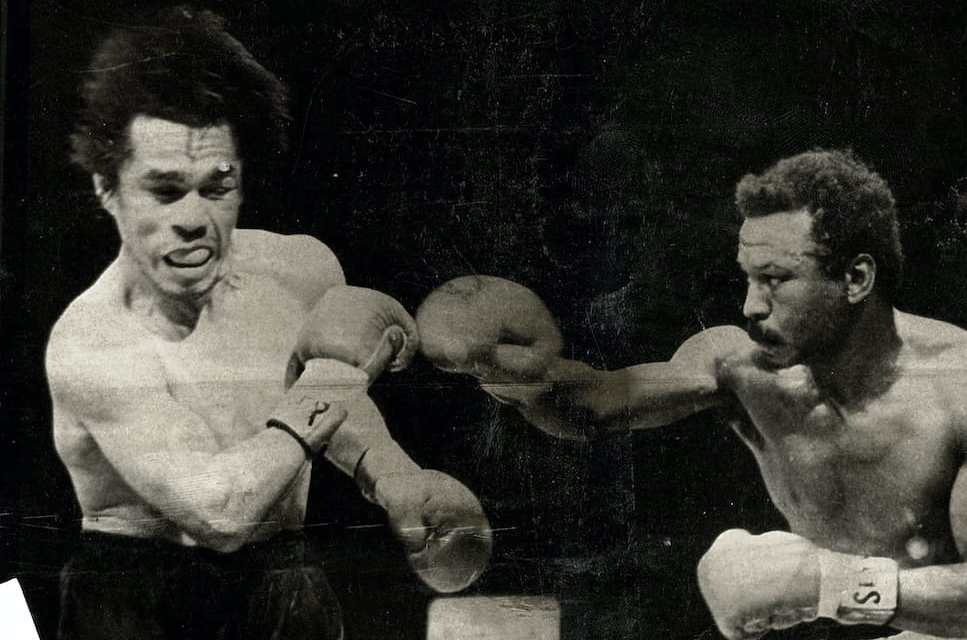

In the middle of those fights, he faced the mythical middleweight king Carlos Monzón in Paris (February 9, 1974, half a century ago) in an inequal duel, because all the advantages were on the southpaw’s side (who weigh 159.9 lbs, against 153.8 lbs), punching power and arm reach. Paradoxically, because of the result against him, it was the most publicised and remembered fight in Naples by the fans of the world, as two legends fought each other. The powerful Argentinian fighter won in seven rounds, but Napoli never looked back. He even later accused Monzon of sticking the thumb of his glove in his eye. The accused, of course, denied what his vanquished rival had said.

On January 8, 1995, that is, 11 years after that fight, the greatest Argentine fighter in history died when he crashed his car on his way back to the prison in his native Santa Fe where he was serving an 11-year sentence for the violent death of his wife, Alicia Muñiz.

The “Mantecas”, as the Mexican press called him, made 4 more fights after Monzón (Lewis, Saldaño and the 2 with Muñiz) and on December 6, 1975 he exposed the 2 crowns against the British John Stracey in the bullring La Monumental in Mexico City. The old and tired 35 year old warrior, with 17 years of constant activity, laid down his weapons at 2’30” of the sixth chapter. He never fought again. He left a record of 81 fights won (some publications say 77), 54 by KO and only 7 defeats, only 4 before the limit, with no draws. In 1982 he was inducted into the Boxing Hall of Fame and in 1990 into the International Hall of Fame in Canastota, NY.

After retirement he devoted himself to bohemian life, gambling and even acted in films alongside the Aztec wrestling idol, El Santo. The money he earned with the gloves soon vanished and he ended up in total poverty, surviving with occasional help. Almost five years ago he left for eternity lightly, as the poet would say, without a penny in his saddlebags and living as a tenant in Ciudad Juárez, although a millionaire in glory. He was, in truth, a great among greats.