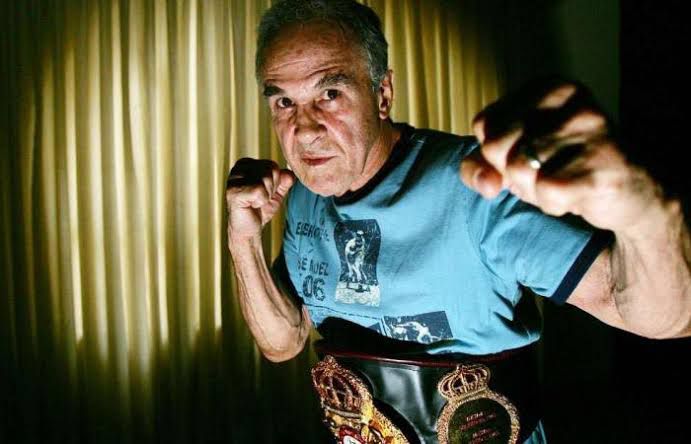

The former Brazilian fighter Eder Jofre, the best bantamweight in history for a large number of experts around the world, let his guard down for good at the age of 86 in the early hours of last Sunday morning in his native Sao Paulo after being hospitalized for a long time suffering from pneumonia, which he was unable to beat, as he did with 72 of the 78 opponents he faced, 50 of which before the limit and only defeated twice on points by the same opponent, the Japanese Masahiko “Fighting” Harada.

The unfortunate circumstance of his death is propitious to attempt a portrait of the first Brazilian world champion; the first and only Brazilian to be immortalized in the Canastota Hall of Fame, since 1992; ninth in The Ring magazine’s list of the hundred best boxers in history.

JOFRE VS ARIAS: AN INCONGRUITY

Before continuing with the objective of “portraying” Jofre in his journey in the ring, we must make a short stop to remember his visit to Caracas of the “Golden bantam” -as his countryman Sebastiao Rui Barbosa baptized him- on the occasion of his fight against Ramon Arias, Ramoncito for his followers, which took place on August 19, 1961 (61 years ago!) in the Estadio Universitario, at more than half full, the second opportunity in which Arias was trying to win a world title after losing a unanimous decision against the Zulian Ramon Arias, The second time Arias tried to win a world title after losing a unanimous decision against the legendary flyweight king, the Argentine Pascual Perez, on April 18, 1958, the first time a Venezuelan fought for a world title, at the Nuevo Circo in Caracas.

A vast sector of the country’s sports press considered that the Jofre versus Arias was a mess, a madness, because the Venezuelan was in total disadvantage and without any chance against a rival that surpassed him in all aspects (height, weight, punch and in the top of conditions). The difference was also noticeable on the scales: the champion stopped the scale at 1173/4 pounds (53,210 kg) and the challenger weighed 114.3/4 pounds (51,850 kg).

Jofre had not lost in 39 performances, 26 of them by KO, with 3 draws. Arias’ record, in contrast, looked pale with his 7 losses, 4 draws and favorable decisions the rest, mostly on the cards. And to top it all off, he was in decline due to his attachment to the rumba and his detachment to the gym.

We remember that the journalist Heberto Castro Pimentel in no less than ten editions of his well-read column “Puntos de Sutura” (Stitches), analyzed Arias’ disadvantages, the absurdity of the fight and concluded with the advice to Arias’ agent and promoter, Rafito Cedeño, to desist from the crazy idea. Cedeño did not listen to him. He was blindly confident in the quality of his boxer and was absolutely sure, in good faith even if deludedly, that Arias would get over the fence of the champion, a vegan of spotless professional life, overwhelmingly, we reiterate, over the Venezuelan.

All the predictions against the Venezuelan were fulfilled the night of the fight. Jofre let the challenger run, allowed him to use his fast but harmless jab at will, and in round 7 he cornered him, punished him with powerful rights and lefts and Arias went down twice, the second time like a heavy bag, for the fatal 10 seconds.

FIVE YEARS ON THE THRONE

We will abbreviate because the story is getting longer in this intention to draw the great South American fighter who recently passed away and who took his first steps in boxing hand in hand with his father, the Argentinean Aristides Jofre, Kid Jofre as a boxer and his trainer as always.

When he visited Caracas, Eder did it in order to defend for the first time the crown, then of the NBA, two years before the creation of the WBA, conquered against the Mexican Eloy Sanchez by KOT in six rounds, on November 18, 1960, in a bout held at the Olympic Auditorium in Los Angeles for the vacancy left by the Aztec Jose (Joe) Becerra.

After beating Arias, he defended the title against the British Johnny Caldwell (18-1-62, GKOT10), the Mexican Herman Marques (4-5-62, KOT10), the also Mexican Jose “El Huitlacoche” Medel (11-9-62, KOT6), the Japanese Katsutoshi Aoki (4-4-63, KOT3), the Filipino Johnny Jamito (18-5-63, RTD11) and the Colombian Bernardo Caraballo (27-11-64). Five years after his consecration, he lost the WBA-WBC belts to Harada, who defeated him by split decision on May 31, 1965 in Nagoya and in the rematch on May 18, 1966 in Tokyo, the following year.

Jofre retired for 3 years. He came back and won 13 victories with 7 knockouts against second level opponents, as featherweight, and on May 5, 1973, he dominated the Cuban-Spanish José Legra to win the WBC featherweight belt, which he risked against Vicente Saldivar, from Mexico, former owner of that same version. After half a dozen irrelevant victories, he left definitively after defeating by DU10 the Aztec Octavio “Famoso” Gomez on a day like next Saturday, 46 years ago. The death of his father, Aristides, in 1974 and of his brother Dogalberto in ’76 brought forward his farewell to the ring.

Just a few lines more, for a historical rectification. Erroneously it has been said that Jofre never went to the canvas. Uncertain. On November 14, 1958, in his early days as a professional, the Argentine José Smecca knocked him down in the second round. Jofre recovered and knocked him out in the seventh.

That was another triumphant song, one of dozens, of the “Golden Bantam”. Who, definitely, has just let his guard down. Rest in peace, champion.