There are not too many regulations in the history of boxing that are as important and transcendent as the 12 Rules of the Marquess of Queensberry which gave a singular impulse and served as a driving force and guide to the discipline of the gloves and the ring.

Next year will be the 160th anniversary of their publication and approval as the dozen of regulations of the activity (five still in force) since they were written by the English trainer and journalist John Graham Chambers, thanks to the patronage of the aristocrat whose name they bear and which were applied since 1865 (some say in 1867), originally in the UK, later in the USA and Canada by 1889, until their extension and knowledge by the rest of the world.

We wrote extensively about this subject more than five years ago, but we bring it up again just for the special knowledge of those who have arrived late to the passion for the sport of fisticuffs.

Therefore, we will try to take a quick and imaginary trip back in time to 1865, the year when those misnamed rules of the IX Marquess of Queensberry, John Sholto Douglas, were born to serve as legal support “to the noble art of self-defense”, English potentate who lent his name to them for posterity and who in fact was nothing more than the sponsor of the new code that consisted, as we have already said, of 12 rules, 5 of which are still preserved, such as 3-4-6-9-11, which have undergone slight modifications with the passing of the time.

For its drafting Graham Chambers took into consideration the 8 original weight categories-now 18, with the newest one being the bridger, located between cruiser and heavyweight, created and still only recognized by the WBC-such are, still in force today, the fly, bantam, feather, lightweight, welter, middle, light heavyweight and heavyweight.

It is worth adding that the Marquis, born in Florence, Italy, of Scottish origin, in 1895 had a loud, angry and prolonged trial with the laureate English writer, Oscar Wilde (The Portrait of Dorian Gray and The Importance of Being Earnest, among his works), whom he accused of being a sodomite because of his sentimental relationship with his son, Lord Alfred Douglas, a lawsuit that sent the writer to prison for a few months. However, in the face of new evidence against him, Wilde was eventually found guilty and sentenced to two years, for which he was financially ruined and died prematurely, perhaps from grief, shortly thereafter. But this is a different story, unrelated to the subject at hand.

Back to the subject, the truth is that the real author of the code was the British trainer and journalist John Graham Chambers, member and founder of the London Amateur Athletic Club, who wrote them in 1863 and made them public 2 years later for their application, made mandatory in 1865, at first only in the United Kingdom, by 1889 in Canada and the United States and since then until today in all countries where boxing is active, which is almost all over the globe.

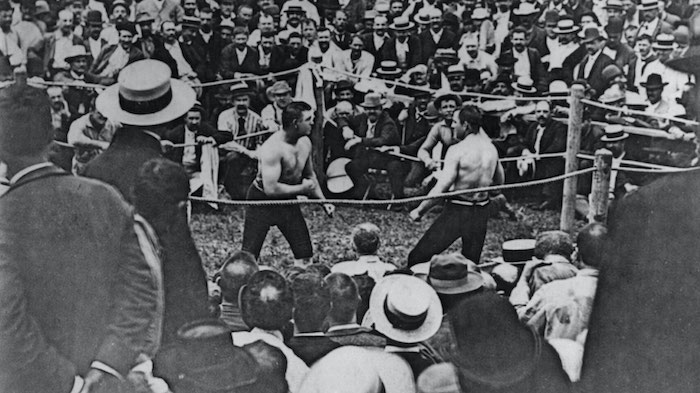

The rules, origin of modern boxing, came to replace the 23 of the London Prize Ring, of 1838 – in turn replacing the 7 of 1743 created by the former heavyweight champion Jack Broughton – and that put an end to the traditional fight with bare hands of 2 centuries ago, as well as with the fights that stopped when one of the opponents fell exhausted or died.

In the dozen rules of Chambers, or Queensberry, as they are better known, apart from the obligatory use of gloves, the 3rd and 4th stand out, referring respectively to the duration of 3 minutes per round with 1 rest and the end of the fight if the fallen fighter does not react or does not get up before the count of 10¨. They remain as they are today and they also humanized to a great extent the sport, since they contributed to reduce, considerably, the risk of death on the ring, which was abundant due to the endless actions of the fights, that ended due to the extreme exhaustion or death of one of the opponents, as we said before.

At this point it is worth mentioning the name of John Lawrence Sullivan (1858-1918), nicknamed ” The Boston Strong Boy”, the first American athlete winner of more than 1 million dollars and the last world champion of the heavyweight bare-knuckle, as well as the first with gloves, an honor that some boxing historians also awarded to James J. Corbett, the only winner of Sullivan, who left the ring with 38 wins, 32 knockouts, 1 loss and 1 draw (36 wins, 32 losses and 1 draw), although some people assign him a record of 41 (36 wins, 32 knockouts, 1 loss and 1 draw). Corbett, Sullivan’s only victor, who left the ring with an unofficial record of 38 wins, 32 knockouts, 1 loss and 1 draw, although some give him a record of 41(36)-1-3.

Sullivan won the belt over Paddy Ryan with a 9 round KO in February 1882 and retained it 7 years later against Jake Kilrain on July 8, 1889 in a fierce 120+ minute bout that Sullivan decided in the 75th round.

Before Kilrain, Sullivan knocked out Dominic McCaffre in Cincinnati on August 29, 1885, in the first gloved fight in history. After 5 more bouts with no belt on the line, and his commitment to Kilrain, he retired in 1889. He returned to blemish his record against Corbett in 21 rounds, on Sept. 7, 1892 at the Olympic Club in New Orleans.

Let’s go back for a few more lines to the real father of the rules, John Graham Chambers, to note that it was he who came up with the idea of raising the ring 35 inches centimeters off the ground (and no more than 48 inches) to offer a better view to the spectators. Originally 24 feet long, with 2 ropes per side, with the passing of the years the ring became 3 ropes per side and then 4 (16 in total).

To conclude, let’s add that at that time the dimensions were fixed between 17′ to 20′, with a height of no less than 3′ and no more than 5′ from the ground.